In the mid-1850s discussion began in the United Kingdom about the ways in which photography might be used to help fight crime. The chief concern was how to make it easier for police to recognise habitual criminals. The rapid expansion of modes of travel such as the railways in the 1830s, had created a problem for police as criminals could now easily move from town to town, committing crimes and then disappearing to a new location. Written descriptions of culprits were insufficient to cope with this new transient criminal.

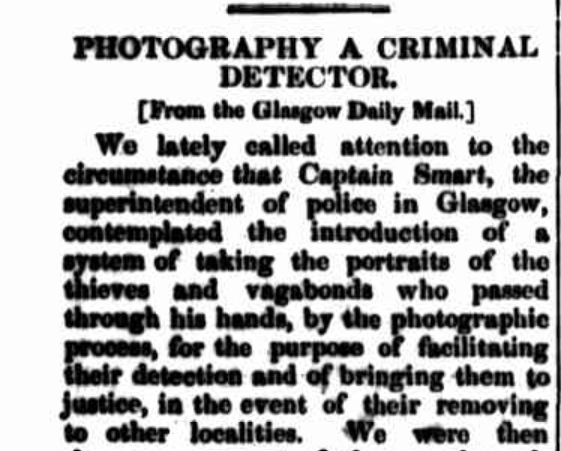

In 1855 the Glasgow Daily Mail reported that the Superintendent of Police, Captain Smart, had been contemplating a method by which the portraits of the ‘thieves and vagabonds’ that crossed the path of Glasgow police could be captured.1 The distribution of photographs of convicted criminals was deemed to be a low-cost alternative to the other idea that had been floated- the development of a national police force whose job it was to travel the country hunting down criminals.

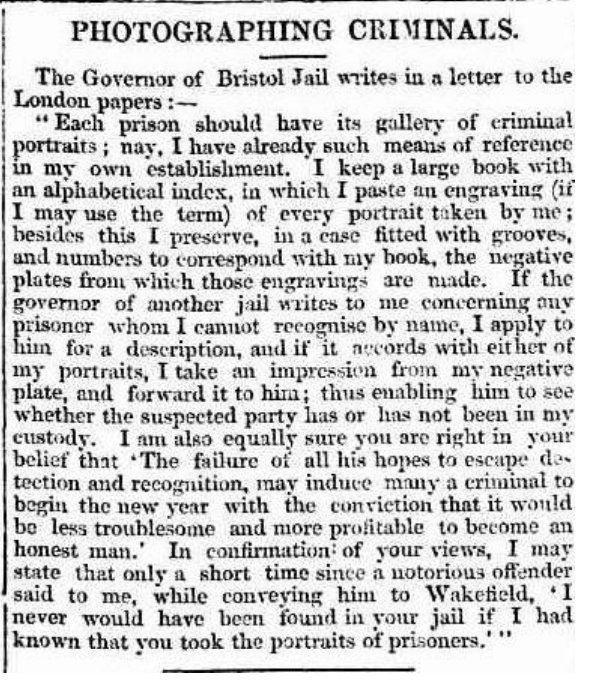

Meanwhile, down in Bristol, the Governor of Bristol Gaol, Mr J.A. Gardiner, had already adopted a scheme for photographing prisoners in his care. Like Captain Smart, he believed that the ‘the most cunning, the most skilled, and the most daring offenders are migratory in their habits’.2 His ambition was to see his system implemented in all prisons across the United Kingdom.

One of the earliest documented instances of photographs being used for identification was in Manchester in 1858, when two boys absconded from a reformatory school. Such institutions were used to rehabilitate juveniles who had committed criminal offences. At the time, it was customary for boys at the reformatory to have their photograph taken on admission.3 The boys’ escape was so well planned that no trace of their whereabouts could be found, and it wasn’t until photographs of the boys were circulated that the escapees were identified and recaptured. Although their recapture was attributed directly to their photographs being taken, the wider implementation of prisoner photographs was slow to be applied, and it wasn’t until the Prevention of Crimes Act was passed in 1871, that photographing of prisoners became common practice in the United Kingdom.

In Australia, developments and debates about the use of photography for the identification of criminals was reported in newspapers, but like the United Kingdom, enthusiasm and action was varied. Some of the earliest adopters of prisoner photographs were New South Wales and Tasmania, both of which had a large population of ex-convicts who required a close watch from police. From the early 1870s, most states in Australia had formally begun photographing of prisoners.

Society through a lens

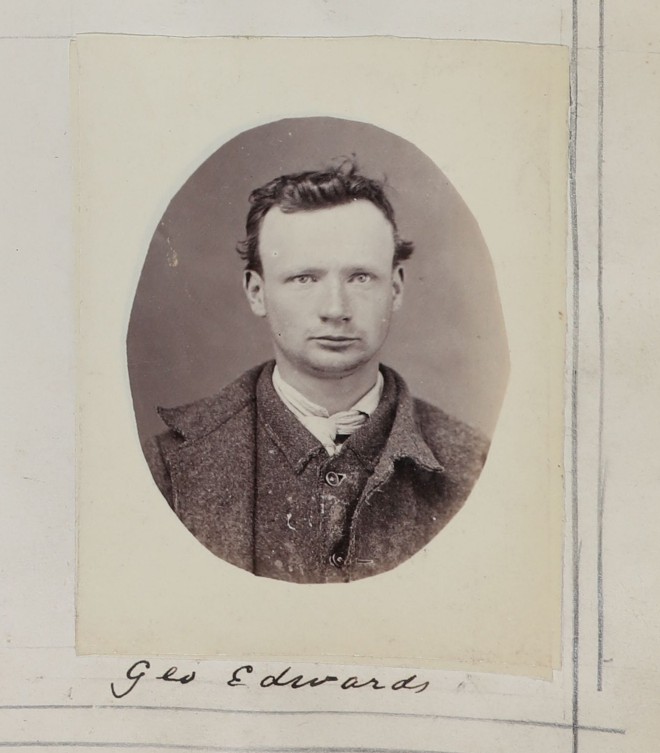

Prisoner photographs help to put a human face to a crime. The misdeeds are no longer just words that appear in a newspaper article or in the Police Gazette– they become real crimes committed by real people. When we consider that photography was an art form that was developing in the nineteenth century and was not readily available to the average person in the way it is for us today, these photographs take on a new significance. Sadly, sometimes these prisoner photographs are the only visual record of a person left behind.

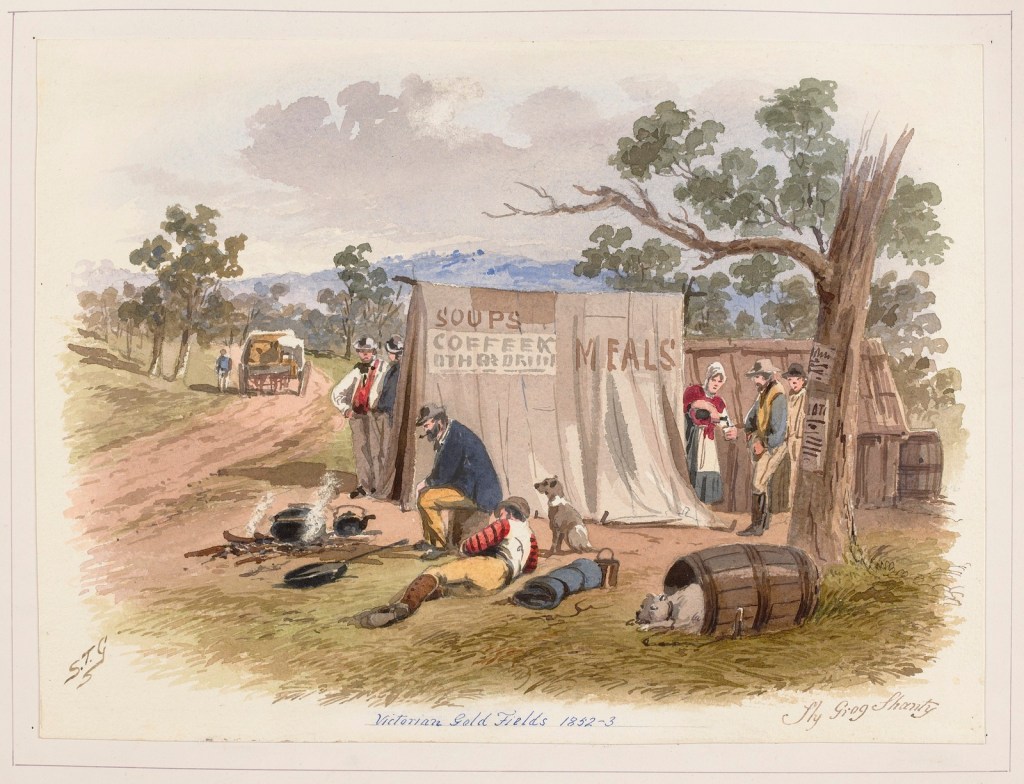

The photographs provide a lens through which researchers can view society in the moment in which the images are taken. For example, some of the women who appear in the pages of the prisoner registers kept by the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), are serving short sentences, a few days, or weeks, for crimes such as vagrancy, or having insufficient means to support themselves. That people in these situations could be incarcerated and treated in the same manner as a thief or a murderer, tells historians something about the way society dealt with those who were experiencing financial difficulty, homelessness, or mental health issues. This was a period before the invention of direct government support schemes, and instead the government offered payments to charitable causes such as benevolent asylums who offered support to ‘deserving’ recipients. It was, therefore, a system where people were penalized and punished for being poor, and this could disproportionately affect women who had less work opportunities than their male counterparts.

Identity

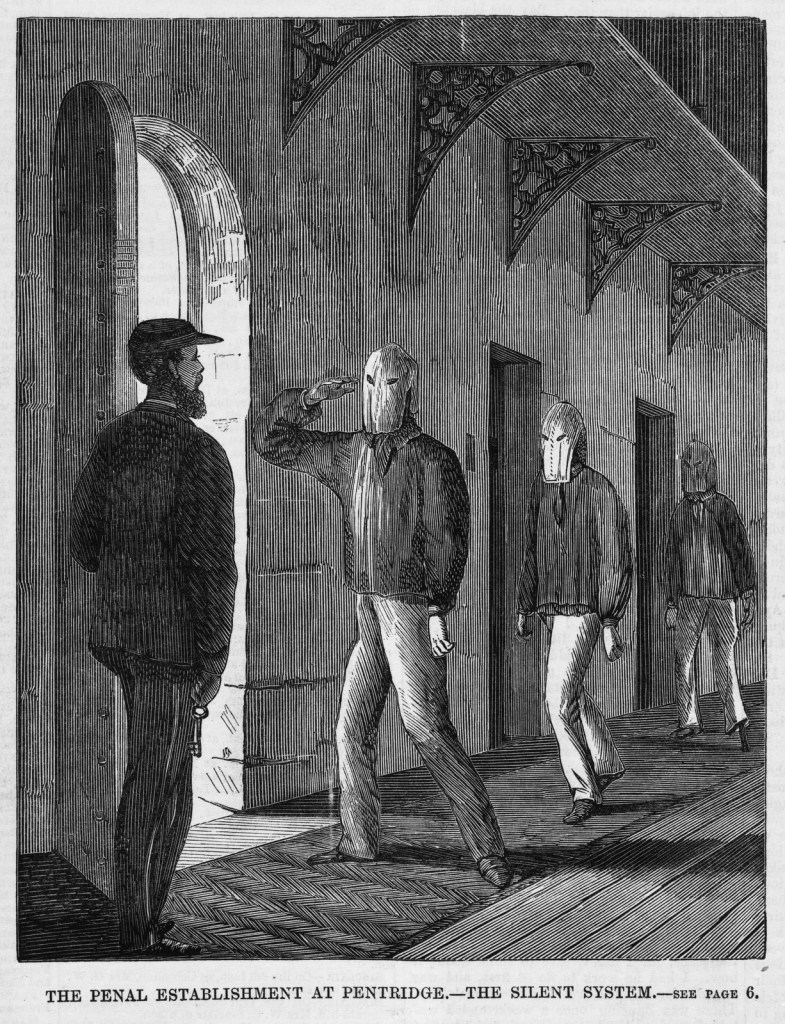

When a prisoner entered the penal system, their identity was stripped away from them. Their name was replaced by a number, and their clothes were substituted for prison garb. Their cell number and the division in which they were serving their sentence would be painted in large font on their clothing. In Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison, ‘A’ Division was for those in solitary confinement (most new inmates started off here as part of their penance for their sins), ‘B’ Division was for inmates who had served time in solitary and were now being put to work, and ‘C’ was for those close to freedom. Early sketches of prisoners at Pentridge show that for the one hour per day that they were allowed to exercise in the prison yard, they had to wear a cloth mask over their face to conceal their identity from other inmates. A similar method was used in England’s notorious Pentonville Prison. The use of masks within prison is an interesting contrast when you consider the lengths police went to to document a person’s identity, which was then completely stripped from them upon entering prison.

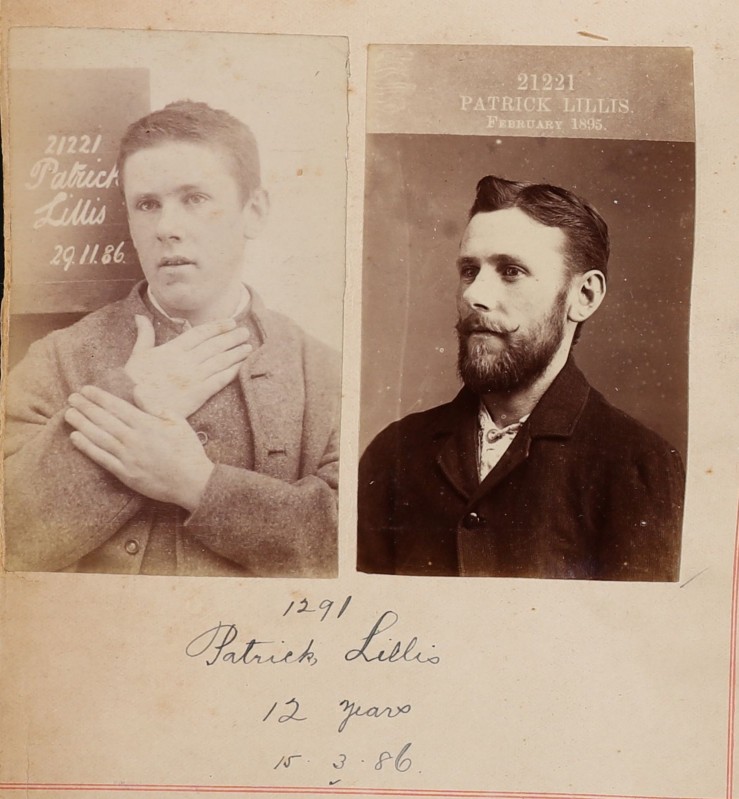

Sometimes, prisoner photographs give us before and after images, showing criminals entering prison, and then a second photograph at the end of their sentence, showing us the passage of time, or the toll that their incarceration has had. The image below is of Patrick Lillis, who was sent to Pentridge at the age of 17 for manslaughter. Lillis had killed his brother-in-law after an incident in which he alleged he was defending his sister who was being beaten by her husband. Of his 12-year sentence, Lillis served just over 9 years and was by all accounts a model prisoner. His small list of offences in prison included ‘knocking on a wall’, ‘having tobacco’ and attending a church service without authority4

In the first image, Lillis is a teenage boy, and in the second he is a young man. Prisoners who were about to be released from prison were allowed to start growing their hair, changing their appearance to make them better able to blend back into society upon their release- another reason why these photographs were so valuable to police, as they would want an updated image of Lillis in order to recognise him should he offend again.

Photography and identification techniques

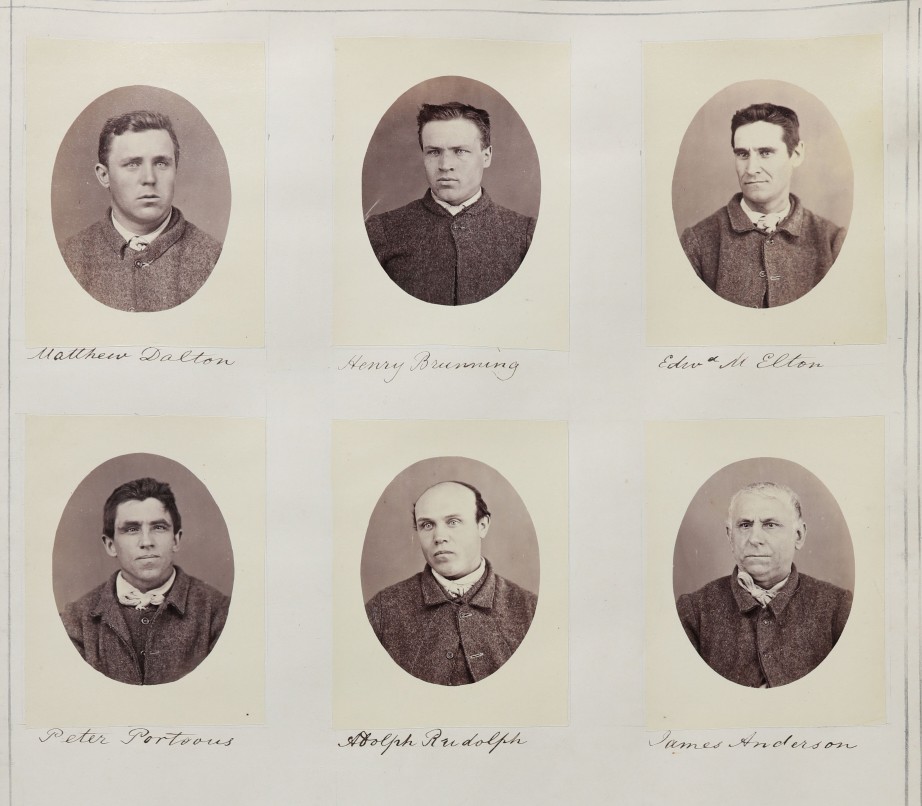

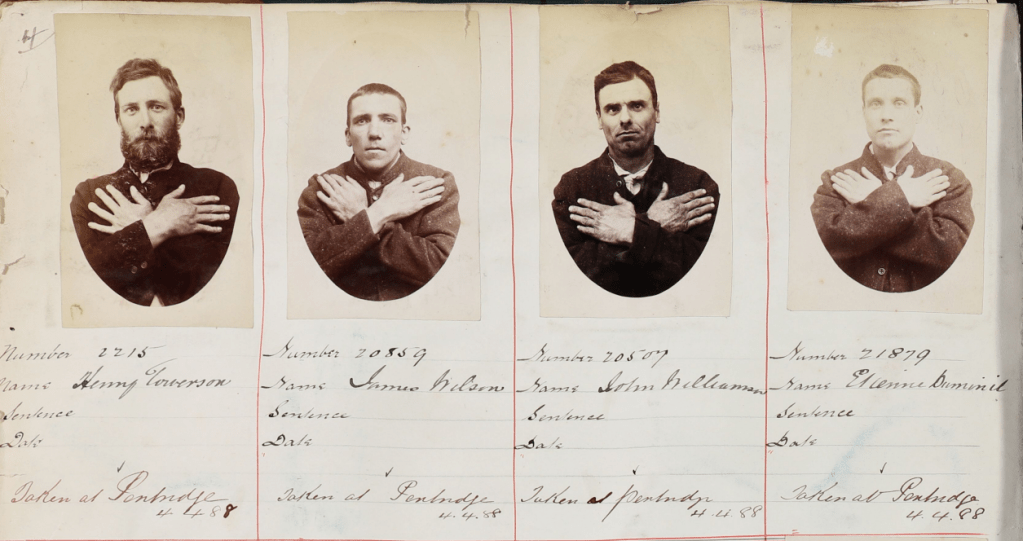

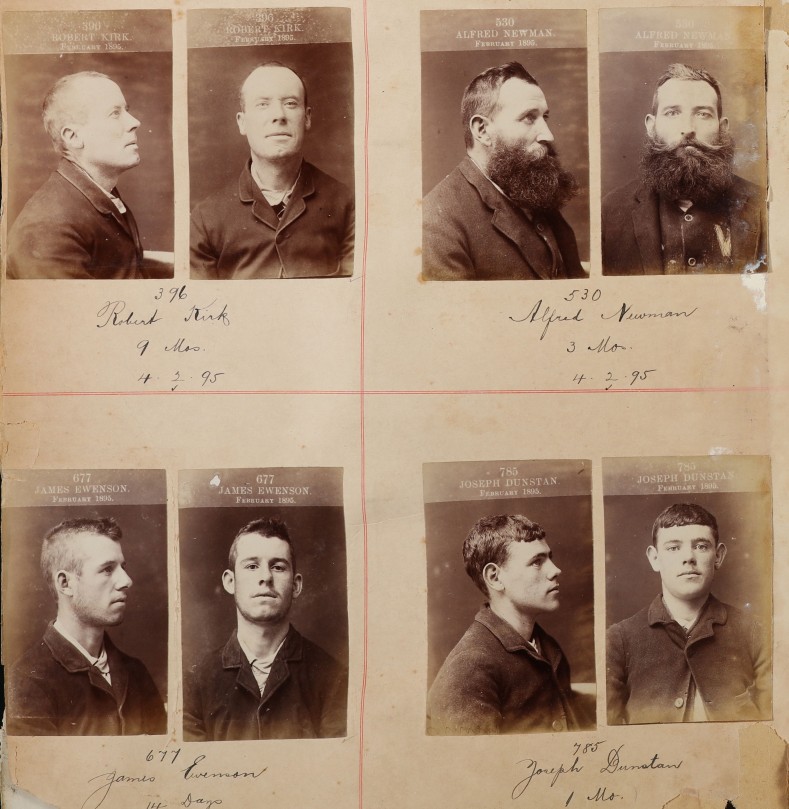

Prisoner photographs also help to chart the development of photography and identification techniques. Early photographs of prisoners were not too dissimilar to the carte de visite style that rose to prominence in the 1860s. These cards were the social media of their day, with sitters having a collection of photographs printed on to cards, which they then gave to friends in a style similar to the Victorian social etiquette of calling cards. Recipients usually kept these cards in a special album, and soon carte de visite were being printed of celebrities and traded in the streets. In early prisoner photographs produced in this style, prisoners are looking slightly to the left or right of the photographer so that an off-centre profile can be captured (like the photographs at the top of this article). It is interesting to think that instead of being traded in the streets or collected in family albums, carte de visite photographs of prisoners were being circulated among police forces across the country for inclusion in ‘rogues galleries’.

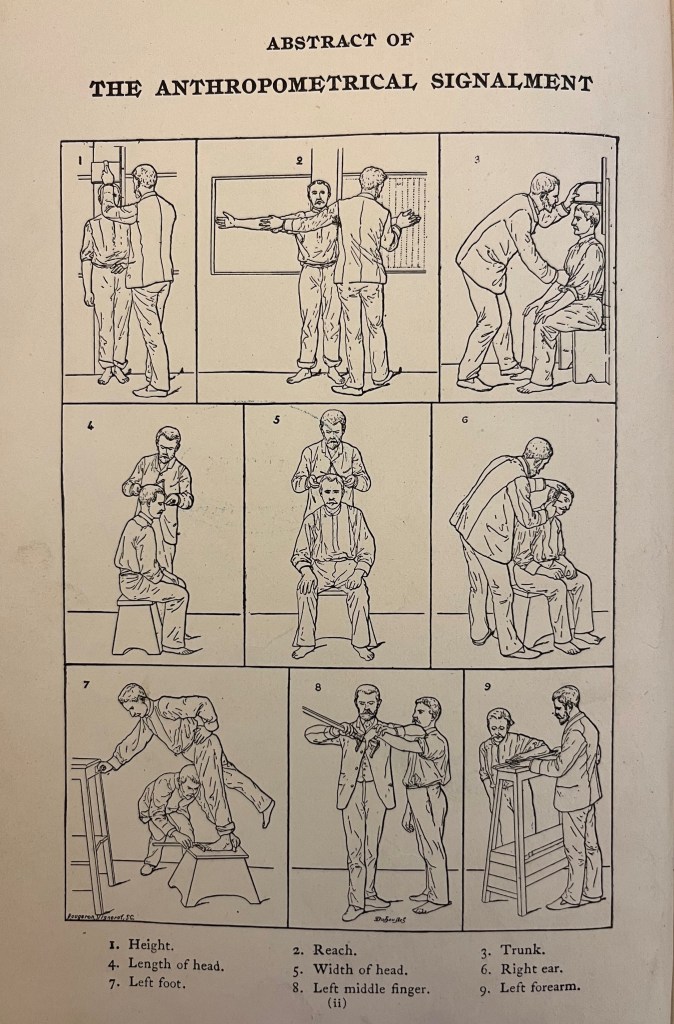

In the late 1870s, Paris police official Alphonse Bertillon invented the first effective modern system of criminal identification.5 He combined prisoner photographs with anthropometric descriptions to provide police with comprehensive profiles of criminals. His system required police to record the measurements of several parts of the body, such as the forearm and the head, which in an adult were unlikely to change. These measurements were written on a card and were combined with a visual description (blonde hair, blue eyes etc), as well as a front and profile photograph of the prisoner. In the photographs above, prisoners show their hands so that any identifying features can be recorded.

Bertillon also devised a classification system for the cards, with the measurements taken creating a numerical sequence that grouped like profiles together, thereby making it easier for police to find matching records. This classification system would be the inspiration for the later method of fingerprint identification which was implemented in the early 1900s in the United Kingdom and Australia.

For his method, Bertillon championed a standardization of photographic techniques to ensure all photographs of prisoners were of the same quality. He recommended a standard focal length, even and consistent lighting, and a fixed distance between the camera and the subject.6 In the prisoner photographs collected at Pentridge and conserved through PROV, we begin to see Bertillon’s influence on the photographs taken.

The influence of Bertillon’s photographic recommendations can be found in modern ‘mugshot’ photographs which still take a front and profile photograph of criminals. Police no longer take limb measurements alongside photographs, as this was replaced by fingerprint identification. By thinking about the ways in which photography could be used to help identify criminals, the way was paved for the use of photography in other areas of policing such as in the photographing of crime scenes and of evidence. The ‘Rogues Gallery’ provide researchers with many angles of investigation, into people, society, institutions and technical advancements, which is why I find them so endlessly fascinating.

References

- From the Glasgow Daily Mail, in Launceston Examiner, 7 April 1855, p 3 ↩︎

- As above ↩︎

- The Courier (Hobart), 29 January 1859, p 2 ↩︎

- Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P0000, Central Register for Male Prisoners 20853 – 21347 (1885-1886). Record for Patrick Lillis. ↩︎

- Bolton, R (ed) (1989), The contest of meaning: critical histories of photography, MIT Press, Cambridge (US), p 353 ↩︎

- Bertillon, A (1896), Signaletic instructions: including the theory and practice of anthropometrical identification (translated from the French and edited under supervision of Major R.W. McClaughry), The Werner Company, Chicago, p 240-242 ↩︎

Leave a comment