When working in a library, you sometimes come across stories in strange ways. I was first introduced to the name Mary Fortune when I was researching well known people who lived in Dunolly in the nineteenth century. I’d been asked by a library user if I could help them find more information about a prostitute named Jane Callaway. While scrolling through the Dunolly Museum website, my eye was caught by the name Mary Helena Fortune, and the description that she was, ‘one of the most mysterious people to ever have lived in this district1‘. Now, friends of mine will know that I can’t help myself when it comes to a mystery, and so I got to work unravelling the story.

The life of Mary Fortune is extremely difficult to summarise in one short blog. She was an extraordinary woman whose personal life was just as interesting as her prolific writing output, and yet her name is relatively unknown. Her writing career spanned half a century and over five hundred short stories. Her genre was mainly crime fiction, under the series title The Detective’s Album, but she also wrote poetry, romances and journalism about life in rural Victoria and the goldfields.

One of the reasons she remains relatively unknown is that she wrote under a variety of pseudonyms, including, M.H.F, Waif Wander, and W.W. These neutral and elusive aliases made her a very hard person to trace in the history books. In recent times, author Lucy Sussex has been at the forefront of unearthing the story of Australia’s first female crime writer.

Originally from Ireland, Mary and her father emigrated to Canada around 1846. Mary’s mother had died when Mary was an infant. In 1851, when Mary was eighteen, she married a surveyor named Joseph Fortune, and not long after, the couple welcomed a son. The marriage likely soured quickly, and when Mary made the long and arduous journey to Australia in 1855, she left her husband behind. This would have been scandalous, not to mention illegal, as at the time, men were considered the rightful custodians of any children in a marriage2. Mary had taken Joseph Fortune’s only son and disappeared. Perhaps this was one of the reasons she would later use aliases in her writing.

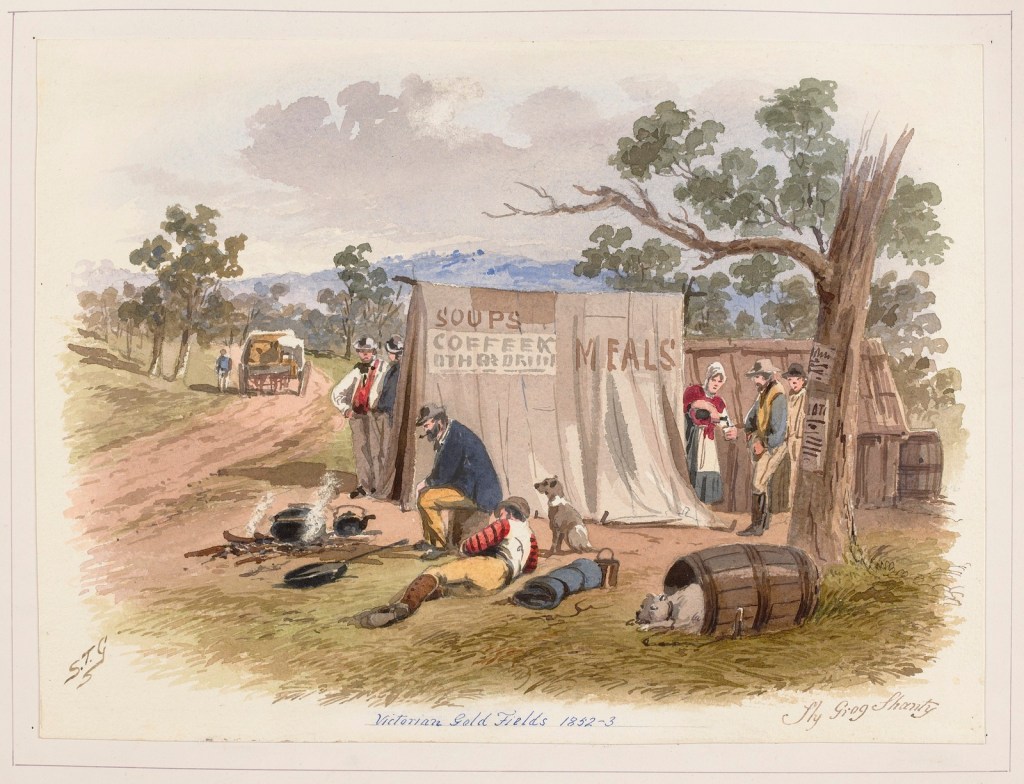

Mary had emigrated to Australia to join her father on the goldfields. George Wilson was a storekeeper who regularly moved around regional Victoria following the boom or bust trends of the gold craze sweeping the area. His store was likely nothing more than a canvas tent, and he would have sold food supplies, but he may also have dealt in sly grog, which was fairly common on the goldfields.

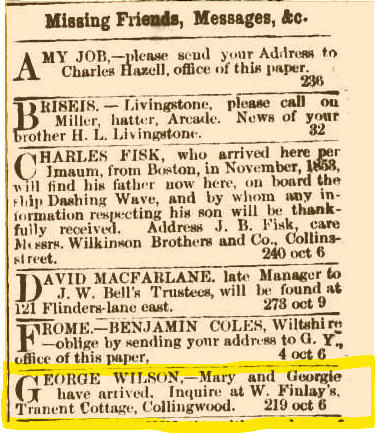

Two days after Mary and her young son arrived in Melbourne on the passenger ship Briseis, she put a notice in The Argus newspaper, announcing her arrival and asking her father George to make contact. This was a standard thing to do for new migrants to the colonies, and early editions of newspapers like The Argus, dedicated columns on their front pages to reuniting ‘missing friends’.

Mary’s writing talents began before her arrival in the colony. Her journey to Victoria had been via Scotland, where she had been commissioned to write about life in Australia for a women’s magazine. Although Mary never fulfilled this commission3, the idea that she could perhaps make some money from writing must have grown from this moment. The exotic foreignness of life in Australia and the harsh realities of life on the goldfields, would provide Mary with ample inspiration.

Through her early poetry Mary reveals something of herself and her life, and her journalism articles are also semi-autobiographical. In these, she takes on a notable role as an unreliable narrator, embellishing and changing details for the sake of a good story, but also presumably to protect her identity. For example, her father is fictionalized in her writing as the characters James Grieve and Uncle Barry.4 This confusion of fact and fiction in her journalism about the goldfields has made the truth of her life even harder for researchers to unravel.

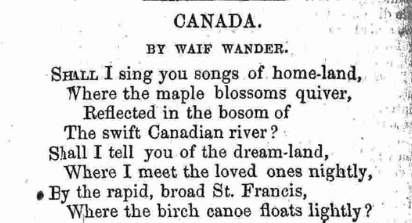

Despite her Irish roots, Mary would always hold a stronger sentimentality for her Canadian girlhood. Under the alias Waif Wander, she published a poem called ‘Canada’ in The Australian Journal in 1866. There is something romantic and wistful about the start of her poem, a kind of longing or homesickness for a landscape she left behind.

For someone who considered herself an outsider to Australian life, Mary seems to have adapted to life in the colony well. Her writing shows a depth of insight into the harsh realities of life here, but also the development of what it meant to be ‘Australian’, incorporating swagmen, bush settings, and wildlife into her published writing. Her detective stories also show an astonishing insight into police procedure, which probably stemmed from her bigamous and short-lived marriage to police constable Percy Rollo Brett, as well as her son’s criminal tendencies. In later life, she had interactions with the police as an informer, and was arrested for drunkenness and vagrancy. Like I said, she is a very interesting woman both personally and professionally.

To say that Mary was a prolific writer would be somewhat of an understatement. From her first appearance in The Australian Journal in 1865, she appears in print consistently, sometimes twice in one issue. For me, it’s her detective stories that have the most appeal. They are extraordinary for their attention to detail and their craftsmanship, not to mention the fact that they were written by a woman in a time when women’s roles were confined to domestic spheres. This is perhaps the second reason that she chose to write under aliases. If she wanted to be considered a serious writer and be published regularly, then assuming a male name would yield better results. At one point, Mary’s writing was considered so good that the Mount Alexander Mail offered her a job as sub-editor, only for them to rescind the offer when they discovered that she was a woman5.

Her work in The Australian Journal appeared alongside what would become pinnacles of early Australian fiction, including the serialised story His Natural Life by Marcus Clarke, which was later published as a novel with the longer title For the Term of His Natural Life. This tale about the brutality of convict life in Australia is a feature story of editions in the early 1870s, and places Mary’s own work in high esteem by association. Her pseudonym was also promoted by the journal as being one of their star contributors.

The life she may have lived, and the notoriety she may have enjoyed will always be a ‘what if’ scenario. What if she had boldly put her own name on her work? What if she had become celebrated alongside her male writing colleagues? What if her name was taught in schools as one of the pioneers of early Australian detective fiction?

To read all of Mary’s detective’s stories featuring the former Mounted Trooper turned detective, Mark Sinclair, you would need to set aside many hours, but if you are wanting to dip your toe into the fictional criminal world of nineteenth century Australia, then I highly recommend the following tales:

Death in the Pot (The Australian Journal, September 1868)

This story immediately appealed to me when I first read it. Why? Well it involves a case of suspected strychnine poisoning, something that was very much on trend in the 1800s. British society was positively awash with cases of poisoning, as strychnine was a fairly common poison found in households and used to kill vermin. Its accessibility made it the perfect poison for domestic murderers. Mary Fortune’s use of it in her short story is fascinating because of the method in which Detective Mark Sinclair extracts the poison in order to solve the case and catch the killer. Intrigued? You’ll have to read it to find out more.

Love (The Australian Journal, October 1869)

Although this story is narrated by Detective Mark Sinclair and is part of the Detective’s Album series, it feels more of a tale in the vein of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, or another Victorian-era saga. It features a tragic tale of an elderly man without a suitable heir to a grand estate who takes in his nephew and a ward. As could be predicted, the wayward nephew and the pretty ward fall in love and elope together, breaking the heart of the elderly man who then pursues them to Australia. For me, this is one of Mary Fortune’s tales that is almost wasted in a short story and could have had a successful turn as a serialised novel, much like many other successful and popular novelists of the time.

The Stolen Deed (the Australian Journal, August 1875)

This short story has all the ingredients of an Agatha Christie or a Sherlock Holmes mystery. A missing deed, an invalid, a warring stepmother and stepson, disguises, and a twist at the end. This is one of Mary’s short stories that feels before its time. You could uproot this 1875 story and plant it in the golden age of crime fiction (a.k.a. the interwar period), and it would still work. One of the elements that I find intriguing about the story is that Detective Mark Sinclair dresses up as a woman to try and nab his thief. A respectable detective traversing Melbourne’s Fitzroy Gardens in petticoats in the 1870s? Seems daringly modern to me!

Recommended reading

For a very brief overview of Mary Fortune’s life and death, you can read a blog on the State Library Victoria website here.

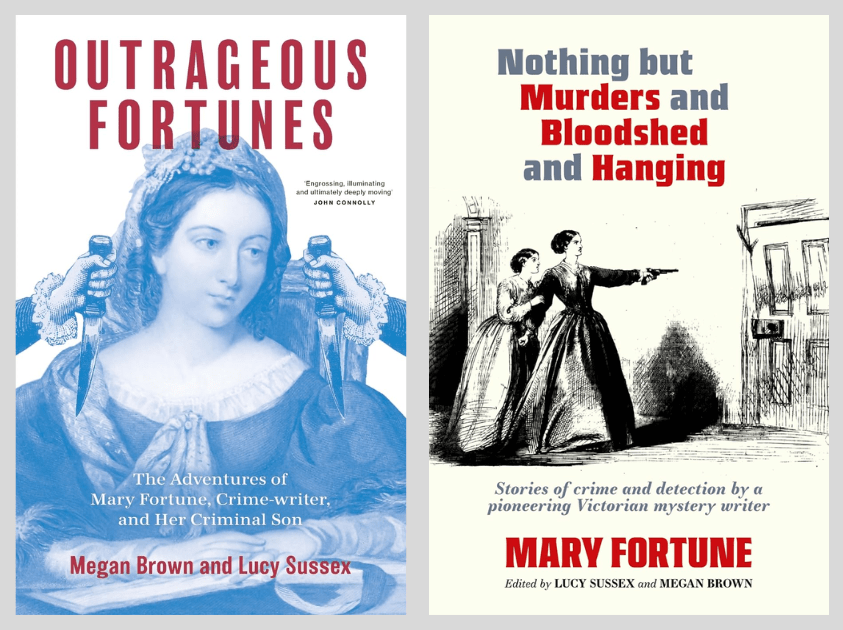

The following books are a must-read for anyone wanting to know more about Mary, her life, and her writing:

- Outrageous Fortunes: The Adventures of Mary Fortune, Crime-writer, and Her Criminal Son George by Lucy Sussex and Megan Brown.

- Nothing But Murders And Bloodshed And Hanging by Mary Fortune, with introduction and notes by Lucy Sussex and Megan Brown.

Top tip: You can read copies of The Australian Journal through State Library Victoria, but also check your local library’s online resources. Lucy Sussex and Elizabeth Gibson have also published a bibliography listing every edition that Mary Fortune appears in. You can find details here.

References

- Dunolly Museum (n.d.) Women of Dunolly: Mary Helena Fortune [website], accessed 12 December 2025 ↩︎

- Sussex, L, and Brown, M (2025), Outrageous Fortunes: The Adventures of Mary Fortune, Crime-writer, and Her Criminal Son, La Trobe University Press, Collingwood, p 15 & 17 ↩︎

- As above, p 21 ↩︎

- Sussex, L (1989), The Fortunes of Mary Fortune, Penguin, Ringwood, p xv ↩︎

- Sussex, L (2005), Fortune, Mary Helena (1833–1911), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, viewed 14 December 2025 ↩︎

Leave a comment